John McKenna reels in the years and finds himself back in Daft Eddie’s in County Down, where it all began.

Daft Eddie’s on Sketrick Island in County Down was an oasis. In the Northern Ireland of the early 1980’s, the cooking that Nick and Kathy Price prepared at this island destination seemed like little short of a miracle. Their food had: Freshness. Originality. Colour. Impishness. Flavour.

In the land of the beef sausage and the soda farl, the Prices brought technicolour to a monochrome food culture.

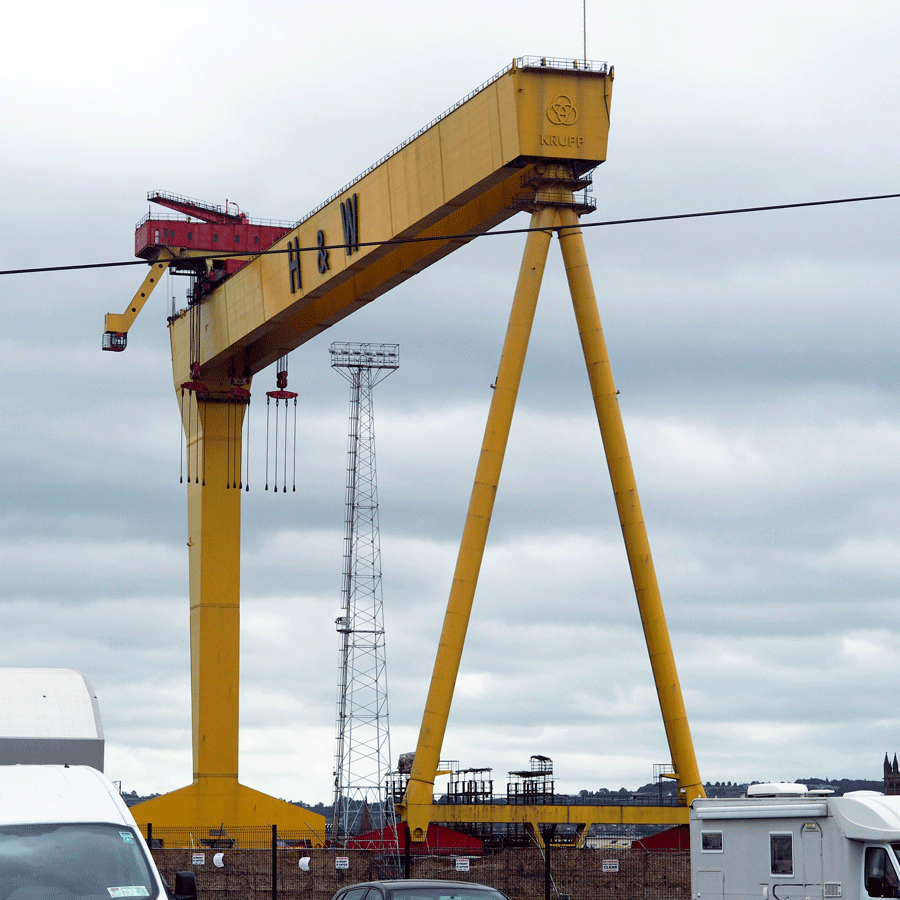

Nick and Cathy moved on to Nick’s in Kilmood and then, in 1989, they managed to get a grant to develop a derelict building in Hill Street, a part of the city now known as the Cathedral Quarter, and a part of the city that was then known as A Place You Didn’t Go. They opened in December, a few months after another couple, Paul and Jeanne Rankin, had opened the doors of their restaurant, Roscoff, in Shaftesbury Square.

We were working on our first Irish Food Guide, driving a £100 Renault 4 around the Province, and one day in Bangor a most brilliant butcher, David Burns, told us of this guy who was asking for “queer gear” up in Belfast. In our 1989 diary the details are written down on the page for Sunday August 6th, but it was certainly a few days earlier: Roscoff, Shaftesbury Sq. (0232) 331532. Paul Rankin. Jeannie (sic) Rankin.

So, off we went, and the diary page for Friday 28th July 1989 details what we ate: minced veal with pasta; red pepper galette with French toast; confit of duck with potato salad. Then roast monkfish with 5spice pepper on wild rice; roast breast of duck; roast chicken in balsamic vinegar. Puddings were strawberries Gavroche; pot of caramel cream; honey and ginger ice cream.

It was a tasty start to a revolution.

Before the Prices and the Rankins shook up the city, the good food was found away from the capital, at George McAlpin’s Ramore in Portrush, or The Barn, in Saintfield. But 1989 gave the city what it needed: serious, creative cooking. And Price and Rankin – and Michael Deane, who would soon open his own place in Helen’s Bay – gave the city another enormous gift: they were great cooks, but also great mentors. Great chefs flourished in their kitchens, none more so than Roscoff, whose alumni is a roll-call of talent unmatched by any other Irish restaurant.

Then the stars trickled into place, the city calmed down and ushered in more peaceful times, and the great restaurants multiplied: Noel McMeel in the Beech Hill in ‘Derry; Robbie and Shirley Millar in Shanks; Cath Gradwell in Alden’s; Deane’s in the city centre; Barry Smyth in The Oriel; Simon Dougan in The Yellow Door; Niall McKenna in James Street South; Paul Arthurs in Kircubbin; Brian McCann in SHU; Danny Millar in Balloo House; Ian Orr in Browns; Stephen Toman in OX; Danni Barry in Eipic.

Just as importantly, the second wave of great chefs has been joined by a confident phalanx of great artisans, people making raw milk blue cheeses; people making sourdough bread; guys roasting coffee beans, a cohort with stratospheric skill sets joining the brilliant butchers, fishmongers and bakers who have always been the backbone of the Northern food culture.

The revolution is tastier than ever.