One of my favourite New Yorker cartoons shows a typically befuddled man, standing on a cloud, and wearing standard-issue heavenly garb: a grand pair of angel's wings, and a calf-length hospital robe.

Standing beside him, and similarly attired, is a cross-looking wife. She is looking over her shoulder, and saying to our hapless-looking angel: 'Here comes God. Ask if we can move to another cloud'.

Heaven. It isn't a place where nothing happens. It's a place where life continues, just as before, complete with nagging wife. Our hapless male angel might have dreamt on earth of a balmy idyll, maybe even replete with dusky virgins and sweet flowing streams such as the martyrs for Islam are promised.

Instead, our New Yorker angel still looks like an exhausted Wall Street banker, and his wife, as he could have predicted, isn't satisfied with her after-life. In The New Yorker, heaven is always a humbling place: the masters of the universe may float transcendentally, but their feet are made of clay.

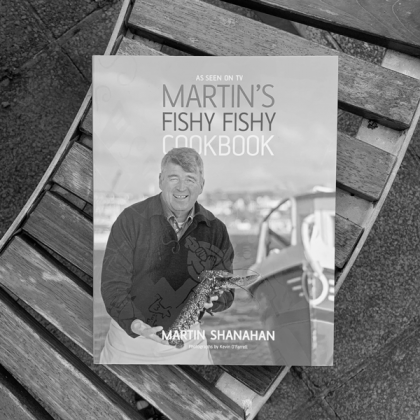

I was thinking about this idea of heaven recently, as I helped out a bit at the launch of Truly Tasty, a book of recipes for people with kidney disease.

The first thought, quite frankly, was one of guilt. In the rere inside page of Truly Tasty there is a little pouch which contains an Organ Donor Card. I wasn't carrying a donor card, and as I mingled at the launch amidst wonderful kidney patients, their nurses and doctors, I felt thoroughly ashamed.

Above all, I was embarassed, especially as I listened to patients speak of their gratitude to the donors whose decision to allow their organs to be harvested for transplants had made the continuation of their life possible. I had never heard people express such profound gratitude, and it was expressed to people they had never had a chance to know.

My embarassment was compounded by the fact that, as a card-carrying atheist, it should be people like myself who have no belief in an after-life who should be the first to be card-carrying donors.

So, with the donor card signed and filed in my wallet, I wondered why we are so reluctant to be organ donors? And this brought me back to our New Yorker angels.

As a loving, and deeply sentimental people, we have become thoroughly wedded to a supernatural idea of heaven. Instead of a place where our souls wait until the day of reckoning, we have recast it as a sort of Sublime family get-together.

Heaven today is like a celestial Electric Picnic, with an audience that includes all our ancestors. And, just like the New Yorker cartoons, in Heaven we look just like we look now, or maybe just as we look after we have been to the hairdresser and had a facial and a manicure.

This is a thoroughly nice idea, but really you wouldn't want to examine it too deeply to know that is has as much substance as those clouds that the angels hang out on in cartoons. And if you were to read a new book by the Princeton professor of philosophy, Mark Johnston, which enjoys the provocative title of “Surviving Death” (It’s the succesor to a volume entitled “Saving God: Religion After Idolatry”. Johnston does good titles), then you would realise that there is a much, much better way of making the most of your potential after-life.

Johnston’s concept for surviving death is a development of John Stuart Mills’ idea that “all who had received the customary amount of moral cultivation would up to the hour of death live ideally in the life of those who are to follow them”.

For Johnston, we can live on “in the onward rush of humankind and not in the supernatural spaces of heaven”. This, asserts the professor, is an altogether better place than 'the supernatural spaces of heaven, even if such spaces existed'.

It’s a lovely idea – the good person who has passed away acquires a new face every time a baby is born — but you don’t need to concern yourself with theology or philosophy to realise one simple thing.

This is that every time an organ donor passes away, and allows the gift of harvesting their organs for others, whether they are patients waiting for kidney, heart, liver or other organ transplants, they facilitate “the onward rush of humankind” in the most practical and immediate way. A death can give life, and not just life but a second life.

It's a no-brainer idea, but do we resist it because of our supernatural, sentimental idea of heaven, where we are recast as a mirror-image of ourselves? If we were really Christian, we would know that the commandment to love our neighbour can be put into action in the most powerful way possible.

One of the most famous New Yorker contributors over the last forty years, Woody Allen, once wrote: 'I don't want to achieve immortality through my work, I want to achieve it by not dying'. Carrying an organ donor card gives you a chance not to die.

The Irish Times Healthplus

Archive - all the best places to eat, shop and stay in Ireland. A local guide to local places.